Was The Beatles' swan song their greatest album?

Super 8: Episode 4

The last album The Beatles ever recorded,

Abbey Road was made at a secret location somewhere in north-west London and may have been their only album recorded entirely to 8-track tape. Nobody’s quite sure to this day where the studio was hidden away, but while we don’t know

where it was made, we do know

how — and that the album was largely recorded onto a 3M M23 8-track machine. Their earlier

Sgt. Pepper… album of 1967 was kind of an 8-track album, in that some songs, such as ‘A Day In The Life’ were recorded on two synchronised 4-track tape decks (both Studer J37 decks I presume). But EMI didn’t install their extensively tested and somewhat modified M23 8-track recorder for use at Abbey Road Studios until 1968, during sessions for

The Beatles. Some of that “White Album” was then recorded to the new 8-track machine, but up to that point the band had been going to Trident Studios to use 8-track tape. Recording the songs for the album that became

Abbey Road began with ‘I Want You (She’s So Heavy)’ in February 1969 — almost as soon as the

Get Back project was abandoned. But it didn’t happen at EMI Abbey Road Studios, because this song was also recorded at Trident.

It was at Trident Studios where they’d used 8-track tape for the very first time: to record part of ‘Hey Jude’ at the end of July ’68 followed by several songs for the White Album. Those songs were of course recorded through the hallowed Sound Techniques console built by Geoff Frost and John Wood. Gear guru Don Larking has gone on record as saying this about the Trident recorder: “Malcolm Toft told me that Trident's first 8-Track machine was a 3M M59, it was the first 8 track machine in the UK. As the 3M was a US machine intended to run on 110 Volts at 60 Hz it needed an external transformer to drop the UK 240 volts to 110 volts to allow it to be used in the UK, but there was no way of increasing the mains frequency from 50Hz to 60Hz so the machine ran slow.” At first the AC frequency was not a huge issue of course, because there were no other 8-track machines in the country so everything recorded on that deck was also mixed and mastered from it at the same speed. Indeed it was Malcom Toft who engineered the ‘Hey Jude’ session at Trident. When it came to mixing that song at Abbey Road and mastering to acetate, the recording sounded dark and “murky” when played back on the M23*.

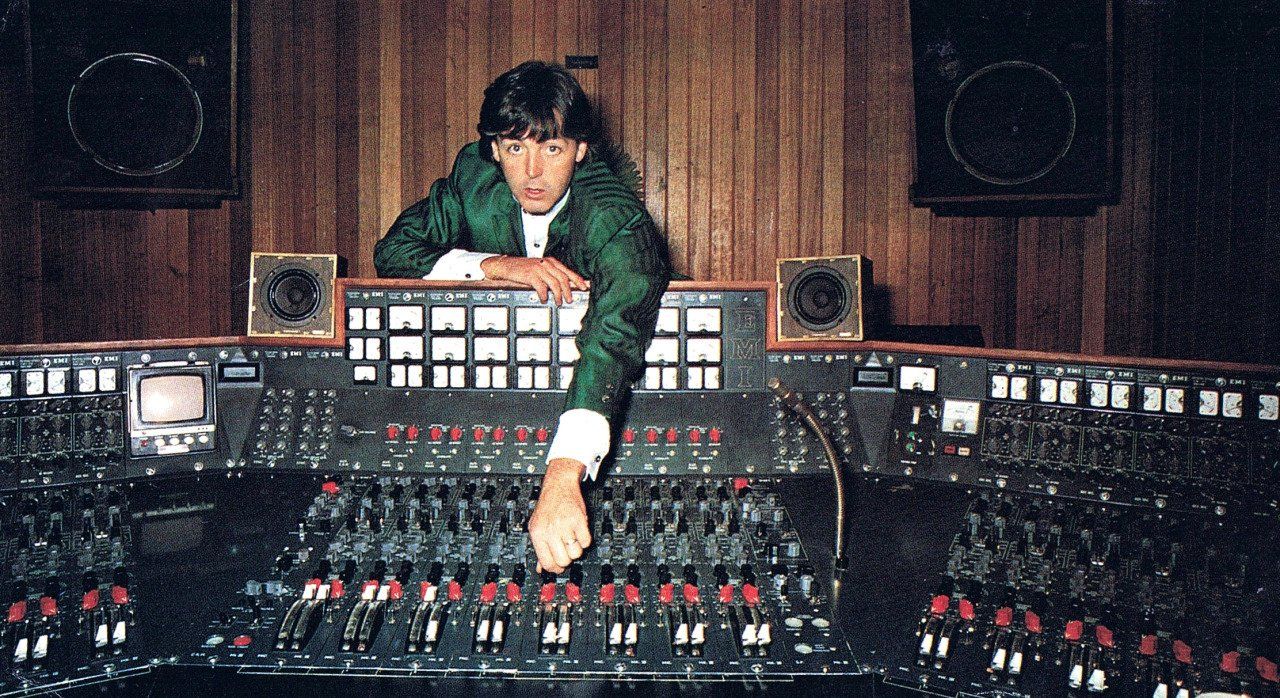

Abbey Road was also the only Beatles album largely recorded through a solid state desk: the EMI TG12345, which had 24 mic channels bussed to 8 tape outputs. It was the MK.IV of this desk that The Dark Side Of The Moon would be recorded through a few years later.

Although it was released before

Let It Be,

Abbey Road was the last album The Beatles made. The song that opens the album with a refrain that initially sounds like a chant of unity, ‘Come Together’ was ironically one of the last songs the group recorded before they fell apart. The Beatles’ demise had been on the cards for some time. In May 1968 the all-but-orphaned Lennon and the motherless McCartney both took up with strong young mums they’d like to fraternise. They wanted to fraternise them so much they wanted to form new bands with them — and give up on the biggest band there’d ever been. Watching Peter Jackson’s

The Beatles: Get Back, Linda Eastman doesn’t look half as comfortable being in the studio as Yoko Ono does, but she was going to have to get used to it. The world at large was largely unaware when

Abbey Road was released that it had a stillborn twin —

Get Back was the Jesse to its Elvis. “Part of the problem eating away at the band’s core was that, although the group had recorded two albums, only one came out… As media personalities and cultural icons of the world’s youth movement, the group continued to fascinate and inspire as well, their hold on the collective unconscious of the counterculture morbidly mirrored by the unchecked spread of the 'Paul Is Dead' rumour across the globe.” (The Unreleased Beatles, p.225, Richie Unterberger. Backbeat Books, 2006.)

Initially all audio for the

Get Back project that would eventually produce the

Let It Be album was recorded onto two mono reel-to-reel Nagra recorders, one for each 16mm camera used to film the Twickenham sessions. The project was supposed to be a bare bones document of a band prepping for a live show. The desire to play the old Rock n’ Roll songs they grew up with — and to record them simply — to get back to where they once belonged, was an attempt to save the band. Like Nirvana going back to Reciprocal before moving on to Pachyderm, if I can draw a parallel here with Episode 1 of this article. But the band weren't satisfied with the quality of the Nagra tapes. Four days into the project George Harrison’s personal 3M 8-track recorder was moved to Twickenham and consoles were discussed. Over ten years ago Unterberger wrote “It’s known that Glyn Johns working separately from the film crew’s Nagra sound equipment, recorded the group (probably in mono) while they were rehearsing at Twickenham January 7-10 (and maybe January 13 too)” (The Unreleased Beatles p.275-6). He went on to say that at the time Beatles scholars didn’t believe they were used in any released form. Thanks to Peter Jackson’s

The Beatles: Get Back project, which I’m watching at time of writing, a lot more of what went on to tape can now be heard, and also seen. When Mal & Kevin are packing up at Twickenham on the 16th Paul drops in to record a quick demo of ‘Oh Darling’ while the recording gear is still set up. Glyn Johns is clearly running a Studer 1” tape deck, which I initially assumed to be a 4-track J37 machine. Possibly they were synching two 4-track recorders as they had done in the past at Abbey Road. This may be the source of later confusion in the Apple Studio when subtitles in the movie make an ill informed statement about ‘syncing’ audio consoles together. Given that the idea of the

Get Back project was to get the band up to speed as a live act and record audio as document, they wouldn’t have needed more than one of EMI’s Record Engineering Development Department valve desks capable of mixing multiple mics into one 4-track recorder in Twickenham.

The difficulties encountered down in Richmond (that resulted in George Harrison walking out and quitting the biggest band in the world) prompted a move to the Saville Row basement at Apple Corps to placate him. But the studio built there by ‘Magic’ Alex was both unorthodox & inadequate. It was also terribly noisy — so much so that in some histories George Martin is said to have brought down two 4-track machines from EMI, presumably both J37s. Some months ago before

The Beatles: Get Back was aired I was speculating that these may have been replaced with an M23 8-track recorder. I found a picture of a tape box (Tape No. E90491) labelled in various ways up on thebeatles.com, and amongst the writing, including 2268 scrawled twice in large figures by different hands, it said APPLE 1, Mach M23 8TR, 24th January 1969. This was confirmed in Jackson’s version of

Get Back — it is clearly stated that Harrison’s 8-track was moved in for the Apple Sessions and there are plenty of shots of an M23 being used; but as I said you can’t rely on these on-screen texts to be entirely accurate.

“He bag production… he got Ono sideboard…”

Although the rest of the gear that was lashed together was moveable and had come from EMI studios in Abbey Road it is definitely not “portable” equipment as described in the subtitles. The desks were modular so that they could be moved more easily: they could be used for location recording but they were not truly portable like the Nagra tape machines. ‘Portable’ of course, from it’s very root, means something that can be carried or worn. In the Apple basement footage Glyn Johns is often to be seen seated at a REDD.37 console but there appears to be another board on the side — what initially looks like a REDD.17 in the background off to his left. At first glance I saw a single pair of VU meters plus peak meter in a housing and thought it was a REDD.17, but as Johns moved in the foreground a second housing of two VUs appeared and there looked to be at least a dozen quadrant faders. Since the .17 only had 8 faders it had to be a later desk — the .37 and .51 both had fourteen Paintons. It has four VU meters which made me think it’s an older version of the .37 desk. It’s too big a board to be a sidecar, but was it being used as a submixer? You get a good look at this second mixer at about 1h:38m of the second episode of

The Beatles: Get Back.

When you get a good look at the second desk, the middle section of the console looks like a .37 apart from the VU meters which are in two pairs separated by what could be a peak meter or talkback unit; and also the modules either side of the fader module are different. As I said, on-screen texts in the

Get Back film say that two 4 channel mixers were “synced together”. Of course they weren’t synchronised because they’re not tape machines, they’re sound mixers

— they do not have separate time elements that might drift apart. Either they were used in parallel or one was a sub-mixer fed into the other, and while the REDD.37 had 4 outputs it was an 8 channel mixer with up to 12 simultaneous inputs through modular TAB/Telefunken valve pre-amps. If the other desk was a .17 then it was built when only two outs were needed for tape decks. But from what I can see in

The Beatles: Get Back I believe both consoles used at Apple each had 12 inputs bussed to 4 tape outputs. I guess the side mixer is just a REDD.37 with a slightly different meter bridge; these things were not mass produced, after all. Or maybe there was actually a REDD.27 console lost to history!

I also spotted a tape machine that I hadn’t heard associated with

Let It Be/Get Back before. About 45 minutes into the 3rd episode of

The Beatles: Get Back we get a few seconds of film of a Telefunken T9 valve tape recorder. In fact, it is clearly a T9U Magnetophon because it’s a 15/30ips machine (where the T9A was only 7½/15ips). The T9 debuted in about 1948 as a 2-track tube tape deck and was made well into the ’60s by the various Telefunken/AEG/Siemens group of companies. The T9 Umschaltbar came along around 1955 (including a 1” 4-track format) and they were often paired with the same Telefunken V72 valve pre-amps that were slotted into the REDD.37 desks (AEG T9A decks are often found with V67 pres). I have read that it was a T9 that Stockhausen used to record

Kontakte (The Computer Music Tutorial, p.373, Curtis Roads; MIT Press.) I had to search all the pictures on reeltoreel.com before I could identify this machine. Perhaps that second REDD desk was feeding the T9U.

“You don’t look different, but you have changed… ”

When

Abbey Road was released there were only 3 months left of the 1960s, a decade like no other; and there were only 7 months left for The Beatles as a band. The final track medley feels like John & Paul emptying their pockets before going their separate ways. But for a band on the run-out groove, they were still pushing the technology to it’s limits. There is a raw energy to

Abbey Road; it isn’t as polished as

Sgt. Pepper’s, nor is it as experimental, but for my money these factors impart immediacy to the songs. Not to mention they faced the added difficulty of Paul McCartney being dead by this point. As many fans have pointed out, you can clearly see his bare feet sticking out from under that white VW Beetle up on the curb on the record cover. Sorry, it’s hard to keep track of the “facts” in the Paul-is-dead fantasy. No-one’s ever been able to adequately explain to me how the three surviving Beatles, having full fiscal control over the McCartney doppelgänger, were unable to persuade Billy Shears to sign with Klein. So, you recruit an exact double to maintain the status quo, or at least your earning potential, and then you allow that employee to start acting like a full partner? “And in the middle of negotiations, You break down”?

Of course McCartney didn’t die in a rogue traffic incident in 1966. It was really Lennon who died like that and was replaced by a double. Which is why the whole Paul-is-dead diversion blew up in 1969 instead of 1966. The real story is that the entire Ono-Lennon clan expired in a car crash in Scotland, on 1 July 1969, at the very moment that Paul was singing “You never give me your money… You only give me your funny paper”**. Yes, I’m taking the piss of course — but come on, if Billy Shears wrote ‘Blackbird’ and ‘Hey Jude’ then he was as good a songwriter as the man who wrote ‘Yesterday’ and ‘Eleanor Rigby’ — and he managed to give them an equivalent disposition. And why would Lennon fire such slings and arrows at Billy Shears in ‘How Do you Sleep?’ especially in the words “Those freaks was right when they said you was dead”? Most of the Paul-Is-Dead hoax “evidence” is laughably deranged. Because it was all in fact a clever spin on the real events of 1966, to disguise a profound transformation McCartney went through. It didn’t happen on a “stupid bloody Tuesday”, though it did blow his mind out in a car.

“You and me, Sunday driving, not arriving…”

What had actually happened back in 1966 was that Paul was body-snatched by space aliens from his Austin Healey 100 at exactly the same time that Bob Dylan was whipped off his Triumph Tiger 100, and then the extraterrestrials swapped their brains around before sending them back to earth***. It’s all in the lyrics to ‘American Pie’, if you’re paying attention, which references all the main Rock N’ Roll alien abductions. Sometimes human evolution needs a bit of outside help, particularly when it comes to our appallingly selfish monkey brains, and music is the best tool for the job. The later consequences of this extraterrestrial interference resulted in George Harrison going off to Byrdcliffe, NY, near Woodstock, to hang out and write with Macca-in-Dylan towards the end of 1968, after Harrison saw the changes in Dylan-in-Macca, as he dumped Jane Asher after the Rishikesh recess and got an American girlfriend instead. It all came to a head a couple of months after that when he 'got back' in January ’69 with Harrison falling out with Dylan-in-Macca during the Twickenham rehearsals, such that he actually quit The Beatles.

George and Paul were school mates at The Inny, they learnt to play guitar together, Paul brought George into John’s band The Quarrymen in 1958. Yet between 1970 and 1994 they barely spoke. George played on John and Ringo’s solo work (including the visceral ‘How Do you Sleep?’ attack on McCartney) but never on Paul’s. Instead he became one of Dylan’s true friends and even formed a new band with him in 1988. In 1985 the man who had invented the pop charity concert in '72 refused to appear at Live Aid and sing 'Let It Be' with Macca. At that Concert for Bangladesh he had invited Dylan to perform with him but not McCartney. In 1975 Harrison was lauding Macca-in-Dylan to the

Melody Maker thus: “Bob Dylan is the most consistent artist there is. Even his stuff which people loathe, I like.” Incontrovertible proof of my theory if you ask me! Of course the aliens’ biggest cranial transplant success was swapping John’s left hemisphere with Yoko’s when they were admitted to the Lawson Memorial Hospital after their Scottish car crash.

I don’t know if people have lost their sense of humour or just their ability to read between the lines, but in the age of "fake news" I feel I have to qualify what I’ve just said by pointing out that I am still ridiculing Beatles conspiracy theories here — by inventing new ones that I personally find far more entertaining. I really shouldn’t have to be so blunt but it seems satire has become redundant in the 21st Century and it feels like the human race is getting dumber by the week. I worry that films like

Idiocracy and

WALL-E might really be prophetic. I'm sure there will be some people who weren't amused by the first couple of sentences of this article. How is it that the most innovative band in the history of popular music got slapped with the most feeble conspiracy theories? Especially when there’s so much scope in The Beatles’ history for intriguing speculation. I can’t be the first person to remark upon the fact that the United Kingdom was changed forever when John Lennon looked into the homes of the nation down the barrel of a TV camera at London Airport on Hallowe’en 1963 and said “I’m not voting for Ted.”

"Ah ah Mr Wilson, ah ah Mr Heath."

The Baby Boomers reaching their majority were paying attention. Almost exactly a year later Ted Heath’s Conservatives lost their first General Election in 13 years to the Labour Party under leader Harold Wilson. Almost exactly a year after that Wilson got The Beatles their MBEs. Unlike his namesake in 1066 Harold won again in 1966, beating Tory leader Ted in the next General Election to remain Prime Minister. His moderate socialist government proceeded to abolish capital punishment and theatre censorship, and to relax the laws on divorce, abortion and homosexuality. These changes were socially seismic: suddenly everyone could behave the way the ruling classes had done for centuries, and also get away with it. Perhaps it wasn't the biggest change to British rule since the Norman Invasion, but it was the biggest change in British society since the Black Death killed half the population. Bubonic plague wiped out somewhere between 100 and 200 million people in the 14th Century and a labour market was established in Western Europe when the peasants suddenly became a commodity in short supply. Using a pandemic as an opportunity for positive change in society, ah, if only.

The cultural revolution in the second half of the 1960s that the UK experienced as a result of these huge shifts in collective freedom had a massive effect on society and behaviour throughout the western world. The ‘British Invasion’ of America wasn’t just about pop music, but also the common concerns of the young people playing it. You can bet your bottom dollar that the influence on young voters that Lennon exhibited at that pivotal moment in 1963 was remarked with disquiet in reactionary circles. Have a think about the synchronicity of Ed Sullivan passing through London Airport on the very same October 31st that Lennon nailed his political colours to the mast. Had he not wondered why this little English band were being met by so many screaming fans and TV cameras, then The Beatles might never have been quite so big a deal in America and 'the British invasion' might never have happened. Not that America hadn’t already been experiencing it’s own re-evaluation of morality with regard to race and gender politics in the aftermath of World War II. And of course if John Lennon hadn’t really survived crashing his Austin Maxi in 1969 there would have been no reason to assassinate him 11 years later.

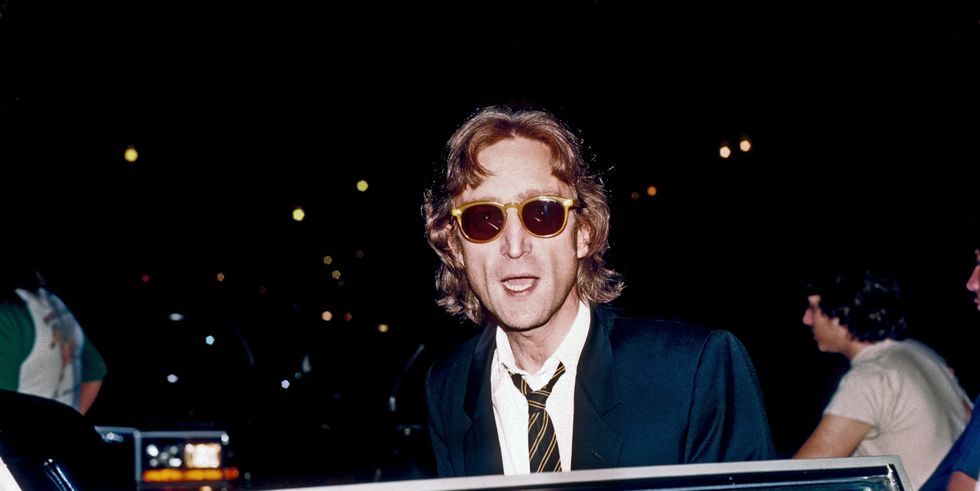

In 1975 John Lennon took 5 years of semi-retirement as a house-husband. On November 17th 1980 he released

Double Fantasy — his first proper album since 1974’s “lost weekend” record

Walls & Bridges. Just three weeks later he was gunned down outside the Dakota. Lennon’s killer got him to sign a copy of the new record on his way out to a meeting. He & Yoko went to talk to David Geffen about the prospects for

Double Fantasy overcoming its poor critical reception. If Lennon had proposed what happened next, as a marketing concept, well, he couldn’t have had a more profitable idea. When he got home from the meeting the same fanatic fired five .38 calibre bullets into his back.

Double Fantasy won the Grammy for Best Album of 1981 and went on to sell triple platinum in the US alone. John Lennon died instantly on the street outside his home. He’d spent most of his last day on earth recording at The Record Plant. He was starting to say something as an artist again. Geffen had to wait another 14 years to get that good a turnaround on a poorly received album after the artist got shot dead. In Utero didn't win a Grammy, but it did go quintuple platinum.

“You know it has been for so many years…”

Let me see now, what other conspiracy theories can I cook up for you. Do you want to know what was really in JFK’s coffin when they buried it at sea on February 18th 1966? Do you think the bronze Handley Brittania casket that already weighed 400lb empty really needed an additional 240lbs of sandbags added to make it sink? Have I told you about Haile Selassie swapping identities with one Rainford Hugh Perry in Jamaica in April 1966? “Legba? Where you been at Slick? He done change his name to Scratch”. Maybe it was more than just identities that were exchanged — like I said, the aliens were doing a lot of brain swapping in ’66 — Space Echo baby. For the booklet to 1997’s

Arkology compilation Perry said “It was only four tracks written on the machine, but I was picking up twenty from the extra-terrestrial squad.” Perry later revealed some of those secrets on his

Jamaican E.T. album****. What else was I going to spill my guts over? Oh yeah, I also know where the acetate of the fourth

Sandinista! record was kept hidden for a while. That’s the one that had the strongest songs

— the one the label wanted to be sides 1 & 2 (and preferably the only two sides), but the band wanted it to be sides 7 & 8 so they perversely buried it.

I digress; as so often happens when talking about The Beatles. It is exceptionally easy to be short-hind-sighted when it comes to the impact The Beatles had on Western music. Nobody had changed the European song form this much since Monteverdi: not Schumann, not even Little Richard. While we’re on the subject, David Hepworth makes some excellent points in his 2008 article ‘The Beatles Were Underrated’ (Nothing Is Real, ch.1, p.3, The Long Shadow Of The Fabs; Hepworth, 2018). Because when it comes down to it, The Beatles weren’t really all that influential, were they? It’s not like anyone remembers who they were these days. They’d long been relegated to the minor leagues of the pop divisions until Peter Jackson came along. As Nik Cohn said in 1969 “Next came the Fab Four, the Moptop Mersey Marvels, and this is the bit I’ve been dreading. I mean what is there possibly left to say on them?” (Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, p.126, Ch.13 The Beatles; Vintage, 1969, 2016). Yeah, nineteen sixty-nine he said that. What indeed. Well, maybe just this: if I'm right in my assessment of John Lennon's political impact, then he was the most influential artist of the 20th Century, helping to push humanity into the 21st — even though he had to stay behind in the old millenium. It's the the kind of martyrdom that makes for a good religion. What do you think — a couple of centuries for a Lennonist creed to take hold? He might end up bigger than Jesus.

I’ve looked at four different albums that were made on 8-track tape machines over these four related articles. If their structure has been a little erratic, well it’s been an erratic couple of years, particularly in The Music Biz. You’ll have to forgive me if I’ve strayed from strict studio protocol, but I believe you should try and amuse yourself in everything you do. I was talking about tape recording and I was talking about concision (even though I haven’t been exactly concise myself). So much of the way we now use unlimited tracks of DAW (and the move away from 24-track tape in the 1990s) is about keeping your options open. It’s about saving every version, it’s about comping what you can’t capture in a great take. It’s about compromise. “Comping” is of course the producer’s shorthand for compiling from separate takes, but it always sounds like compromising to me. I learnt to do it with a razor blade back in the ‘80s. When comping was a difficult thing to achieve from taped performances

—

physically cutting and splicing multitrack tape

—

it was almost a last resort. It was "destructive editing". You did it when your artist just couldn’t get that main vocal right, even with drop ins. As for the rest of the band

— if they couldn’t do it in the first few goes then you’d sack them and get someone who could. Why do you think The Wrecking Crew was formed? But these days of course comping is standard practice, and I understand why. With a DAW it's a piece of piss. But here’s the thing, if you’re comping from several good takes, from several good performances, from the same session, then you’ll probably get good results. Do I need to make reference to silk purses and sow’s ears? Well, just as long as you think about it. As long as you have a word with yourself about what you’re trying to achieve. Lightning in a bottle

— you can’t fake it from a strobe light in a dreary drizzle. You need the storm to rage.

There have been some great recordings released over the years that have the odd howling bum note in there somewhere. I think maybe these days young people getting into making music might have difficulty in understanding how that could happen. In the age of Autotune and quantising it is standard practice to give every record the fake smile of tooth veneers, the frozen death mask of botox, the dead ‘perfection’ of a mannequin. Have a listen to the full length version of 'Move On Up' by Curtis Mayfield, there are some howlers played by the brass section. ‘Why was it even pressed?’ I hear the youngsters cry. Because it is a phenomenal performance, because the energy is palpable, because you can feel the joy in the room. There is absolutely no way that the incredible precipitando of Ike & Tina Turner’s version of ‘Proud Mary’ could have been assembled from different takes. Here’s Johnny Cash talking about recording with Sam Phillips at Sun records: “We both felt that if the performance was really there at the heart of the song, it didn’t really matter much if there were some little musical error or glitch in the track somewhere… Sam didn’t care that much: he’d much rather have soul, fire, and heart than technical perfection.” (Cowboys And Indies by Gareth Murphy; Ch.9, p.96) In the words of Neil Young’s old buddy and legendary producer David Briggs: “In those days everybody knew they had to go in, get their dick hard at the same time and deliver. And three hours later they walked out the fuckin’ door with a record in their pocket, man.” (Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography, p.264; Jimmy McDonough. Vintage 2003)

We have that quote framed on our control room wall, it's an approach we try to encourage our clients to take. And that’s what music is really all about. Which might seem alien in a world where turd polishing has become a career path in many fields of artistic endeavour. Is that why people won’t pay for music anymore? Because so often these days it’s a mediocre collage? Let’s consult the Wizard of Waukesha for a final bit of advice, because it’s a sentiment echoed by all the greats of recorded music at one time or another:

“I invented multi-tracking, so I know that you can record parts separately and punch things in, but I don’t do that. My thinking is that a song has to have one feeling, and when you punch in, you’ve got one feeling over here, another feeling in the middle, and something different near the end. When you piece it together, that’s what comes out—pieces. The feeling doesn’t flow. Now, I’m not saying that you shouldn’t punch in if you missed a note. I’m just saying that, generally speaking, a song sounds better and more alive as a continuous performance of how you’re feeling.” — Les Paul, December 2005, http://lespaulremembered.com.

‘Most Likely You Go Your Way And I'll Go Mine’

Remember that quote attributed to Quincy Jones? “The act of multitrack recording is the act of arranging.” Which really should make you think about recording in compositional terms; to think about having a plan on paper or in your head as you go along. Having a limited number of tracks doesn’t mean you have to have your creativity limited. In many ways it focuses you more on how to perform as a musician and commit to artistic decisions. Mixing separately mic’d drums for example, or all your keyboard sounds, down to a pre-mixed stereo pair; bouncing down harmony BVs say, or doubled guitar parts; are all ways of freeing up more space for other instruments, as well as unifying particular voices or ranges in a song. It’s an approach that requires you to make mixing decisions early in the process and whoever’s wearing the producer’s hat needs to have an overview of the project. To record this way, as they did back in the day, musicians need to be well rehearsed. An overall ‘sound’ or character needs to be conceived of

— even if it’s initially based on some other classic album for inspiration. The trouble is you need a bit of vision (and maybe a pencil & paper) to keep track of what’s going where on the tape.

For that towering 1966 landmark in Pop music

Pet Sounds Brian Wilson recorded The Wrecking Crew’s accompaniment to 4-track tape (possibly on a Scully), bounced the entire backing track down to a mono mix onto one track of the custom built 8-track machine at Columbia’s Hollywood studio (Ampex 351 with four PR10s?) — and then used the remaining 7 tracks for vocal harmonies once the other Beach Boys got back off tour. Each of the six singers had their own track, with the occasional extra harmonic ‘sweetener’ instrument laid down on the 7th; because the human voice was that important an instrument for Brian Wilson *****. "On this logistically complex project that became

Pet Sounds, Wilson also began using Columbia’s eight-track facilities for recording vocal harmonies. Byrds front man Roger McGuinn remembered how, at the time, 'the eight-track was in Columbia’s L.A. studio [but] the engineers were afraid of it-they had a handwritten sign taped on to it that said BIG BASTARD'

". (Cowboys And Indies

by Gareth Murphy; Ch.14, p.153)

Dave Stewart was also definitely of the opinion that capturing the power of one very particular instrument was far more important in great recording than the number of channels you used, when he wrote: “With Eurythmics, and with all my productions, I’m one of those old-fashioned record producers who likes to make music around the voice…. People want to hear and feel the emotion in the human voice, and for me that’s the most important thing to get right. There came a point in music when you could have forty-eight tracks, then seventy-two tracks or so, and just create a giant wall of music. And not a good wall of sound, like Phil Spector’s — which was crafted always around the singer — but just a big wall with no dynamics, that would overcome the voice. I believed in following the voice on its journey, and that’s still my thing. The success of Adele is no surprise, as everything is built around her voice.”

—

(Sweet Dreams Are Made Of This: A Life In Music, Dave Stewart; New American Library; 2016). I refer you to Episode 2 of this article for the ways in which Annie Lennox's voice was complimented in ingenious ways.

So, from Les Paul’s 5258 through Nirvana’s 5050, Eurythmics’ 80-8 to the White Stripes’ A80 and of course The Beatles M23 (skidoo); I’ve tried to chart a path through the mists of time, to map out a guide to how and why a restricted number of analogue record-tracks might be a beneficial limitation when it comes to making a classic album. Les Paul had something interesting to say about just how elaborate the recording process would become: “Modern recording equipment is much more complicated than it needs to be. One of the first things I learned in the multitrack business is that the machine can run away from you. It can run you, instead of you running the machine.” And he said that in December 1977 — 14 years before Pro Tools came along. You know, if you need more than 8 tracks you can have as many as you want here at New Cut Studios, we also subscribe to Pro Tools Ultimate. So we can put your music through a UAD A800 virtual Studer tape emulation — or we can just mix down out of Pro Tools to our actual Studer A80 tape machine. Or you could try, as pointed out in Episode 1 of this short series, to limit yourselves to our Otari 8-track with all it’s analogue mojo. But I'll leave with maybe the most important question, as Les Paul once asked of John Hanti: “So does Pro Tools smell like iron oxide on a two-inch tape?”

* I haven’t been able to find any info on the M59 online but the M56 and M79 decks get quite a lot of coverage. Certainly the M79 was built in an 8-track configuration. Here at New Cut Studios we have Don and the legendary Larking’s List to thank for sourcing our 32 channel Neotek console which, coincidentally, was previously owned by John Wood. Check out the

Music from big, pink moons, Floyds and sausages blog on this website for the heritage of our studio desk

— as well as a bit more history about John Wood and Sound Techniques.

** Take 30, the version of ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ recorded in Studio 2 Abbey Road on July 1st, does not have the outro refrain of “All good children go to heaven” that Paul added later when he heard that Julian and Kyoko had died in Sutherland along with their parents. Really… too soon? What are you people like… they were fine, Kyoko had to have four stitches and Julian was treated for shock at Lawson Memorial Hospital in Golspie. As an outpost of the Lawson Station convenience stores/alien monitoring stations it was the perfect hospital for a cover up by the Japanese government.

*** Yeah, yeah, yeah, McCartney’s Big Healey was a 3000 not a 100-6, but the first rule of urban mythology is to spin the facts just enough to turn simple coincidences into believable causalities. Then sprinkle on a large pinch of the improbable, something along these lines:

Not long after the success of the the Dylan-McCartney exchange to trigger the recording of

Revolver and a new direction for the band, the same body snatching ETs visited The Beatles during their 1966 tour of Japan, partly to coach Lennon in his condemnation of the Vietnam war. Sadly the increased UFO activity over Mount Fuji during 1966 caused several commercial airline crashes. But the main mission the aliens had for the Fab Four was to annoy Imelda Marcos by stealing some shoes as a distraction while the aliens removed some of Yamashita’s gold from her husband’s secret vault. As a reward, The Beatles were enlightened by the extraterrestrials during their stop-over in Delhi.

See? it’s easy. First you select a bunch of factual events that could have suspicious circumstances. Then you just have to join the dots in a different sequence and still make a picture.

**** Lee Scratch Perry has died this week (at time of writing) and I am glad to see that his contribution to popular music has been noted and celebrated. For me he is up there with George Martin, Quincy Jones and Brian Eno in the history of recorded music. I didn’t really know Lee, and only worked with him a few times when I worked for some of the On-U Sound acts in the early Nineties — recruited as I was by international man of mystery Kell The Boy. But I have fond memories of watching Lee run conceptual circles around people with his "antic disposition". I saw him give an interview backstage at the 1995 Cactus Jazz Festival in Bruges while The Upsetter hung upside down from a tree and lectured the journalist on the importance of remembering our simian origins, “Hugging up the big monkey man”. The Black Arkist was crazy like a fox and shrewder than many people gave him credit for. He was Anansie, he was Wakdjunkaga, he was the Cairibbean Dalí, and he definitely knew a hawk from a handsaw.

***** Post Scripts:

“Hey Joe, where you going with that gun in your hand?”

Incidentally Brian Wilson was one of the few failures the extraterrestrials had in 1966 with their pop genius brain transplant program. After Pet Sounds Wilson was a prime target for Alien abduction and trepanning. They initially tried to swap Brian’s brain with Phil Spector’s but there was violent tissue rejection and the operation had to be reversed. It did affect both men psychologically though, as well as creatively. In an attempt to salvage the program the aliens opened up Spector’s skull again when they tried to match him up with self-proclaimed necromancer Joe Meek. It’s no coincidence that both Meek and Spector would murder a woman with a gun before they died. The operation went horribly wrong and just a few months later Joe killed his eclectic landlady, and then blew his own head off with a 12-bore shotgun. Conspiracy theorists claim this was done post mortem to obliterate the evidence of alien trepanning in his cracked cranium. Spector had to adopt a series of bizarre wigs to disguise the scars to his scalp — which he blamed on a car crash he had a few years later. Spector was working with John Lennon on his

Rock ’n’ Roll covers album, when he claimed to have had a car crash in December 1973, as an excuse for not giving up the master tapes. The sessions for the album at A & M Studios in Hollywood had been fraught with heavy drinking, gun play and assorted drug abuse. Lennon had to reproduce the recordings a year later at the Record Plant in NYC. God only knows where Brian Wilson went in 1966 but he took a long time to try and get back. It was a long, long time before he could raise a Smile. I guess he just wasn’t made for those times. OK I'll stop now.

‘That’ll Be The Day'

As the momentous events of 1966 mounted up it all became too much for Joe Meek, and he committed murder-suicide at the start of 1967, on the third of February, “the day the music died”. Like I said it’s all in ‘American Pie’ if you read it right. "February made Meek shiver" — the third was a date that had tormented him for nearly a decade. It’s well documented that Joe Meek had been a year early when he predicted Buddy Holly’s death on February 3rd 1958 and that he tried to warn Holly on several occasions. Even though he was off by 12 months in auguring that Buddy’s plane would auger in to a frozen field just outside Clear Lake, IA, he was haunted by the ghost of prescience. He was convinced that photographs hanging in his studio were trying to communicate with him. telling him he was a victim of industrial espionage by the likes of Phil Spector. Instead of spectres trying to talk to him from the walls Spector actually tried to talk to him on a call. When Phil phoned Joe for real, Meek accused Spector of stealing his ideas, hung up on him and then smashed the telephone to pieces.

Hatful of Holloway, (head full of Holly)

The aliens had been messing with Meek’s head long before the Spector swap attempt. They’d been trying for about a decade by this point, initially experimenting with a cerebral teleportation device called Telstar, before resorting to surgical transplants. Joe himself claimed on several occasions that his obsession with outer space was the result of being controlled by aliens. The ETs first latched onto Meek when he was a radar operator in the RAF in the early ’50s and in their attempts to communicate he could “hear a new world”. By the time Meek was ensconced in the crowded studio he called The Bathroom in a flat above Shenton’s Leather Goods store at 304 Holloway Road, his head was stuffed full of ideas about audio engineering and sci-fi nonsense, and he was now claiming Buddy Holly gave him musical and commercial advice from beyond the grave. And for a time his odd business model really was successful. His huge hit ‘Telstar’ in 1962 was the first single by a British group to top the American hit parade: something that wouldn’t happen again until two years later with ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’. There were plenty of things he couldn't see coming however. Meek missed out on having that hit himself, turning down The Beatles, supposedly on four separate occasions, (so maybe everyone should cut Dick Rowe some slack) and telling Brian Epstein he was wasting his time. He also misjudged the potential of space oddity and future star man David Bowie who made his first recording at Meeksville Sound with The Konrads, not long after he fell to earth.

Dandy Ward Hole

Joe was tuned in to music he was receiving from the spheres, but before Meek could inherit the unearthly there was a price to pay. Early alien attempts at neurological teleportation in the late ‘50s hadn’t worked so well. They completely failed to bodyswap Meek with Les Paul, only managing to make Les record a version of Joe's song 'Put A Ring On My Finger'. Another early failure was trying at a distance to swap Joe Meek into Little Richard. On October 3rd 1957 during a flight from Melbourne to Sydney Richard’s plane was buzzed by a UFO. Richard said of the event that the plane would have crashed had it not been borne up by 'angels'. When the UFO appeared again the next night during his show, in the sky over the Sydney Stadium, Richard got truly scared. People tried to tell chicken ‘Little’ it was the launch of Sputnik he was really seeing. The ETs failed to swap the pop personalities but It caused Richard to cancel the rest of the tour, announce a religious conversion and quit show business to join a ministry. He headed for home on an earlier flight: his faith in his extraterrestrial epiphany vindicated when the plane he should have been on later crashed into the Pacific. The effect on Meek was no less disruptive. He started haunting graveyards trying to record disembodied voices; and public conveniences trying to experience more bodily communion. He developed a fascination for Aleister Crowley and the Ordo Templi Orientis which he passed on to a young session guitarist he employed by the name of Jimmy Page. He was now living in a violent demi-monde of speed fuelled cottaging, with the Kray Twins trying to muscle in on his operation. People close to him said he was just amphetamine paranoid as his behaviour became increasingly violent. He got in a punch up with Tom Jones when 'The Groans' turned down his physical advances. Sometime in 1964 he tried to force soon-to-be Hendrix drummer Mitch Mitchell to play a drum pattern the way he wanted by pointing a shotgun at his head. "Hey Joe, where you..?" Wherever it was it was a very dark place.

©️ Mark Vickers August 2022