Kicking pedals…

… and casting Pearls before sine waves.

When you’re trying to fatten up those drum sounds, a useful trick is to apply some subtle overdrive to the tracks, either on individual instruments or across the whole set. But be careful with that distortion, you’re looking to embiggen those beats and get more impact with tasteful crunch — fizzy mush just doesn’t work well with the percussive elements of your mix. Haunting mids in the rack tom resonances and transparent colour in the tone palette, that’s what you’re after. Aren’t you? Now there are plenty of plug-ins out there that will help you to emulate flattering FET boosting or vintage valve compressor soft clipping, but have you thought about how we used to do it? These days of course all you have to do is select your Carmine app on your pocket device and set up a chain that goes something like Krupa-Supraphonic-Starclassic-Sabian-Klon; then make it play 'When The Levee Loops' and you’re done! But back in the day we knew that when it came to drum distortion it was best to do it at source. That way you got interactive drive and organic grunt from playing the effect. Plugging your tom-toms direct into a Tube Screamer gave you all the midrange fatness you could wish for. And of course if you were going to use discrete effects it was better to look to the units actually made by drum manufacturers and optimised for percussive sound. Pearl, Gretsch, Yamaha, all the big beat builders made renowned effects pedals specifically for drums — most particularly, varieties of overdrives.

There are also some rare devices out there and some of the best drum pedals are lost to the mists of time. How about the Slingerland Rolling Thunder that Philthy Animal Taylor famously used on the

Bomber album? Or that rarest of beasts the Sonor Tonreich — I bet even pedal aficionado Josh Scott of JHS Pedals doesn’t have one of those. Compared with guitarists, bassists or even keyboardists, effects pedals were never as popular with drummists. After all, they usually have a much bigger expense than most musicians do when starting out, just to afford the basic instruments. Effects pedals designed for drums were rare and sales were low, so inevitably some of the older drum stomp boxes are difficult to find. I have heard people say that the Tonreich is actually a mythical beast, that was stillborn in the development phase and buried in an unmarked enclosure. Well, more of that later…

Dirt For Drums

There’s a bit of a fashion these days for putting real drums through effects pedals, but as I’d like to illustrate in this article, it’s far from being a new thing. Of course it’s no secret that drums have nearly always been processed, at least from the earliest days of recording popular music anyway. Echo & reverberation, gating & compression: as soon as these techniques for processing audio signals were developed engineers applied them to drum tracks and started to work out ways of using them that soon became standard tricks of the trade. Easier of course to put a drum machine through a pedal, than a full acoustic drum set. By the time our core was getting hard and industrial in the early Eighties we were putting an Oberheim DMX through an original ProCo RAT to make our pretty hate machines. But I reckon people don’t realise how deep the connection between drums and effects pedals really goes. The Pearl OD-05, designed in 1981, is a great overdrive pedal not dissimilar to a Tube Screamer (and with twice the complement of JRC4558 chips), but with the addition of a rather nifty parametric equalizer inserted before the clipping stage. This feature was of course an absolute necessity on a pedal designed for drums. Now, this EQ was almost identical to the midrange control on Lab Series L5 amplifiers* and allowed 15db of cut or boost over a range of 100Hz - 4KHz. It is an exceptionally tunable tone control for an overdrive pedal. Actually Maxon later introduced a mid boost control on the Ibanez ST-9 Super Tube Screamer in 1984. “Urgh — crank up the mids”, to catchphrase Connor4Real. Like, without the cut feature of a true parametric control? Just in case you felt your Tube Screamer needed more mid-range. Okay, I’ll just leave it there.

Since being founded the Pearl Musical Instrument Company have largely concentrated on making excellent quality drums and percussion, and though their electronic output is more limited (we’ll talk about the Syncussion a little later), they made some real lost gems in the 1980s that are only starting to be searched out now. Pearl first tried their hand at pedals in the early Seventies under the brand name Vorg, though the pedals were also labeled with "The Pearl Musical Instrument Co." The Vorg Model F-502 Warp Sound was famously used, not by a drummer, but by a starship commander in 1979's Star Trek: The Motion Picture. I'm joking of course, everybody knows it was the F-501 phaser in Star Trek. Seriously though, the Vorg Warp Sound is notable for being used by Irish-American experimental guitarist Kevin ‘Bloody’ Shields***. The Vorg range also included the F-501 Phase Shifter, F-503 Graphic Equalizer and a model F-504 Flanger that was twice the size of the other pedals and also had the supplementary title Analog Delay Effect. Pearl later restyled these pedals cosmetically — well anyway, around 1977 the beige and taupe boxes got painted black and the Pearl logo replaced the Vorg badge. The black versions are known as the 600 series (F-602, F-601, F603 & F-604 respectively), but they also added another double-wide stomp in the F-605 Electro Echo which had the secondary name Analog Delay. And indeed it was a superb bucket-brigade delay utilising the Mitsubishi MN3005 chip for 4096-stage long delay, but with it’s input & output level selectors for matching to keyboards, this pedal was much more like a synthesiser module. And, the F-605 Electro Echo was also a Chorus pedal that resembled the legendary Boss CE-1 Chorus Ensemble. Both effects could be engaged separately or in unison by a 3-way slide switch labelled Delay, Chorus, Duplex. Come down to New Cut Studios and try out our original Boss CE-1 if you’ve never experienced a real Chorus Ensemble. However the impact of the Boss Compacts, also released in 1977, made units like the Pearl 600 series look antiquated, and so...

At the start of the 1980s Pearl brought out the much more compact Sound Spice pedals, which included the OD-05 - though, as we’ll see later they kept the double-width pedal concept as well (including a CE-22 Chorus Ensemble). These more modern looking floor ‘effectors’ were developed and made for Pearl by a company called KLM, much in the same way that Ibanez used the Nisshin Onpa company, with it’s Maxon brand, to develop their pedals. It was remarkably lateral thinking for a Japanese drum manufacturer to commission a Dutch airline to do their pedal designs. The pedals designed by KLM were certainly influenced by existing devices from Boss, Ibanez and others, but they also sought to innovate and improve on the standard models that the market had thrown up already. The Pearl OC-07 Octave was just about the best tracking analogue octave pedal ever made, it was far superior to Boss’ OC-2 (Ace from Skunk Anansie was a longtime user of the OC-07). In fact, not until 2005 when digital devices like the original, full-size POG came along, could the OC-07 be beaten by anything smaller than a 3U rack from Eventide. If you’re lucky enough to own both the OD-05 and OC-07 (which we do here at New Cut Studios) you can chain them on drums for some fantastic thickening.

Another great ’80s Over Drive from a drum department was the Yamaha OD-10M II, from their SDS range which was introduced in 1986. Construction was sturdy and they had control knobs set well below the level of the foot-switch to protect them from those leaden-footed drummers unlikely to look before they stomp. We have an OD-10M II at New Cut as well if you’d like to come down and try it out. It’s a really great, full sounding overdrive and it stays pretty flat and transparent across the range — with none of the mid-hump flattery that a Tube Screamer could give your toms, so if you’re crazy enough to use it on guitar make sure you’ve got articulate pickups and a good amp. Looking through Yamaha catalogues of the time I can see why the SDS pedals worked so well in use with their EPS electronic drums. The sample based PTX8 brain had 8 individual jack outputs in addition to it’s main stereo pair, making addition of the effects pedals a breeze compared to plugging in real drums. The advantage of using the PTX8 at the heart of a Yamaha D8 rig was that unlike their PMC1 it wasn’t just a trigger module but a tone generator as well. Each of the 8 trigger inputs had it’s own separate sound source based on 12-bit companded PCM wave memory synthesis. But we’re running ahead of ourselves here. We’ll look at the development of drum machines and trigger-pad systems a little later. For now suffice to say that drum electronics go back quite a way - and drum machines even further, as far back as the 13th century in fact. No no, thirteenth… Yes… We’ll get to that as well. I know I joked about putting a guitar through this Yamaha Overdrive, but I’ve actually tried it and it does work remarkably well. It has a full, well rounded sound with thickness and character, without being woolly, mushy or harsh. It is fairly flat across the range with both warmth and clarity even at high drive level. So why isn’t it as famous as a Tube Screamer? Because of it’s terrible name/slash/number? (Too many slashes? taking the piss?). Or because it was designed for drums? Or perhaps because in the Eighties everybody wanted that radio friendly mid-boost on their guitars as much as they did on their drums.

Talking of dated drive sounds, the very first dedicated drum dirt pedal was of course the Gretsch Controfuzz, and it had quite a unique design. Introduced, I believe, around 1971 it put dual LM748 op-amp distortion into the hands of drummers, or rather, it put it at their feet. “Contro” for control presumably, rather than “contra” to imply a bass register, though it did have good low end facility. The unique feature that the Controfuzz had at the time was it’s blend circuit which allowed you to introduce more or less dirt in parallel to the clean signal with the Distort knob. The only other pot was labelled Boost and was the output level control for the mixed signal. To be clear, the Distort control alters neither the gain, nor the clipping amount, of the distorted signal. The circuit is set at maximum distortion and this control actually governs how much of that distortion is taken away from the mix to clean signal. This allows a setting where playing harder pushes more of the clean signal in the mix above the distortion, but with no signal the clean & dirty sides of the audio cancel each other out. It is almost a gated sound with a hard crisp attack that decays with an increasingly fuzzy tail. How can anyone imagine that this wasn’t designed for drums? Of course this character to the device means that it doesn’t work well across the whole drum set. The best implementation back in the 70s was to use several Contros through that early pedal loop switcher the Maestro Multiplier MM-1, allowing you to put individual drums in the set through it’s own Controfuzz. If you couldn’t manage such a complex (at least for the ‘70s) drum electronics set up you could always move to the larger 18v version of the pedal that was the Gretsch Expandafuzz. This pedal combined the Controfuzz with their 3 band Expandatone equaliser. With 3 separate footswitches (in addition to Fuzz) to engage Bass, Mid-range & Treble controls independently in any combination — whether the fuzz was engaged or not — this was a pretty useful pedal to put across the whole kit. Especially when you discovered that the 3 EQ bands worked on whatever audio was going through the pedal, clean and distorted, or whatever other effects were chained with it.

That early Seventies line of Gretsch effects also included the Tremofect, the Freq Faze and the Tone Divider. The appearance & construction of the tremolo and the two fuzz pedals are consistent and clearly part of the same product range. (This also included the Expander-G amplifier with a 5-way footswitch that accessed it’s compliment of onboard effects, including the Controfuzz with Expandatone, Tremofect, and a reverb). Despite the fact that some people have put late ’60s dates to units listed with online sales sites, these pedals have all the hallmarks of early ’70s manufacture. Looking up the Expandafuzz patent # 3,719,782 online I found it was filed in 1971 and granted in 1973 which fits very well with the parts and fabrication. Produced under the Baldwin ownership years, these effects share some details with Maestro units. Could these USA made pedals have been manufactured by Maestro? Certainly the Italian musical electronics firm Jen were an OEM for the Gretsch brand, just around the same time they were making the Vox V800 series pedals, or certainly soon afterwards. Jen made the Playboy series of effects for the Gretsch brand, the line including the HF Modulator, the Dynamics Sustainer, the Harmon Booster and the Jumbo Fuzz. Most of the Playboy pedals were housed in the same sand-cast enclosures they had used for the classic Vox version of the Tone Bender and it’s twin the Jen Fuzz, but instead of rotary pots, all featured a control panel set into the top with three sliders. We have a late ’60s Jen Fuzz Tone Bender at New Cut, though it’s not really a drum pedal. There was also a V846 Vox style wah “made exclusively for” Gretsch’s Playboy range by Jen.

Other Drum Stomps

Of course not all effects pedals that were designed for drums were fuzz boxes. There was the Tama Tank Compander, for example, which pretty much did what it said on the tin. It was a compressor/expander, gate and digital reverb ‘tank’ in one box. Rather than a compander’s common usage in noise reduction (or for digital audio data compression as in the PTX8 discussed above), the Tama pedal was all about sound augmentation and it gave you those big ’80s drum sounds at the kick of a button. Instant Phil Collins - if you had the chops, it had the chips. The audio was converted to digital at the input and the resulting PCM signal could then be processed through a quality chipset which was pretty much the best DSP available when it was released in 1988. The stereo outs were even on balanced jacks for running straight into the board if you were short on DIs. There were plenty of studio rack units at the time that could do similar stuff, but no one had put all of this into one box, let alone a floor unit. The Tank Comp had a large enclosure by ’80s standards (partly due to it having 8 knobs), but it was really no bigger than many of the bulkier ’70s effect pedals.

Talking of drum pedals with specifications ahead of the curve, the Mapex DDE2000 Drum Echo, was a digital delay unit for drums made in Taiwan in the 1980s. Internally it was remarkably similar to the Aria DD-X20 delay pedal (another pedal from the ‘80s that we have at New Cut Studios). Between it’s 2 second maximum delay length and it’s hold feature the DD-X20 was the first proper looper pedal that you could play over. It had three different latch and hold settings selectable by a rotary switch. The Mapex version came in a much larger box with a couple of extra features. Externally it looked a lot like the earlier Pearl F-605 Electro Echo analogue device, maybe there were a bunch of these chassis left over after Pearl condensed their effects into the compact Sound Spice range. The DDE2000’s five knobs turned two rotary switches that gave settings for Range and Hold, and three potentiometers that gave you control over Time, Feedback & Level. The only real difference in the controls between the Mapex 2000 and Aria X20 are the order of the controls on the box. The Mapex’s pots were in reverse order to the Aria and the two switch knobs came before them, instead of on the bottom row. The Range/mS switch (the Aria Range control was labelled msec) had settings labelled 3-15, 16-80, 80-400 and 400-2000. The Hold switch positions were marked as Hold Off, Delay Off-Hold, Delay On-Hold, and Latch (Off, D.Off <—> Hold, D.On <—> Hold and Latched on the Aria). The DDE2000 had stereo output jacks like Tama’s Tank Compander, but also had an input for a 4-way remote foot switch for the latch/hold modes so that the drummer could place it next to his kick or hat pedals. Just like the Aria delay it had a Boss type, tip negative, DC socket. I bought my DD-X20 in the mid ’80s and seem to remember that it would eat up batteries, so the Mapex variant was no doubt equally power hungry.

Rhythmatics

I said that we’d take a look at Pearl’s foray into rhythm electronica and so… Pearl got involved with electronic drums in 1979 with the fantastic Syncussion SY-1. The Pearl Syncussion is one of the great drum machines of the era, whose reputation only really grew significantly in later years. This analogue synth console had two separate inputs that could be triggered by anything with a CV or trigger out, including other drum machines. It was sold with a pair of bongo like drum shells with transducers inside, a 12v DC PSU and a rather flimsy plastic case for the brain, like that for a Hohner Melodica. Even though it was only notably used at the time for some terrible disco clichés, it could really produce some great sounds with a much deeper bass response than a TR-808. So much so that revamped versions of the SY-1 were brought out by both PsyCo X and The Human Comparator in kit form a few years ago. But Pearl also produced percussive electronics and developed their own drum pads as well. When they brought out their DRX-1 in 1985 it was pretty much a copy of the Simmons SDS5: with hexagonal pads, rack mount brain and hardware. It did however manage to sound significantly better than it’s Simmons antecedent. Not that the Simmons kit was the first of it’s kind by any means. The first rubber trigger-pad, electronic drum kit was actually built in 1970 by The Moody Blues’ drummer Graeme Edge with the help of Sussex University electronics professor Brian Groves. It was followed by the first commercial electronic kit in 1976’s Pollard Syndrum before the iconic, hexagonal Simmons SDS5 arrived in 1981.

“Drummers, what a pain in the arse they are, I mean if they didn’t already have a van for their oversize instruments that could also transport the whole band, they wouldn’t get employed at all would they? You’d be better off with a robot, and safer too, even a killer robot.” Variations on this theme are remarks usually born of frustration, but they are some times heartfelt. I mean, everybody tried to get rid of their drummer in the ‘80s didn’t they? And thanks to technology they could. But let’s ignore all the drummer jokes for the moment, I think we need to give our rhythmic friends credit where credit is due. The skill and dedication needed to become a good drummer is rare and valued. Which is why when you find a good drummer, trying to schedule rehearsal is a nightmare, because they are usually found playing in several bands. We’ve all heard the results of what happened in the seventies when the attempt was made to make drums sound like they were played by Hal 9000. Even Steely Dan (a band who stole everybody's drummers) did it on 1980’s Gaucho — and they had their pick from Porcaro, Purdie and Gadd. At the same time that Roger Linn was bringing his LM-1 to market (which was the first commercially available sample based drum machine), another Roger had been building the same thing — but with a far higher spec and at much greater expense. Legendary studio engineer and long time Dan cohort ‘The Immortal’ Roger Nichols, began his recording career tracking and bouncing his classmate Frank Zappa on a domestic reel-to-reel deck. In 1968 he quit the San Onofre nuclear plant (a job that his degree in Nuclear Physics from Oregon State had led him to) in order to run his own recording facility at Quantum Studios in Torrance, CA.

By the time Donald Fagen was asking him to apply his computer skills to achieving the perfect rhythm track for Hey Nineteen Nichols had designed and built an exceptional drum machine. Like Linn’s drum it was an 8-bit sample based rhythm computer, but with state-of-the-art memory and a much better handle than LM-1. They called it Wendel, and in order to achieve metronomic precision but with groove and swing (“the right amount of layback” in Nichols’ words), Wendel used multi-samples with different velocities and emphases. Nichols revealed that instead of a single hi-hat sample, for example, Wendel could draw on 16 different ones in order to vary his inflections. Interviewed by Brian Sweet for his 1994 book Steely Dan: Reelin’ In The Years, Nichols described it thus: “The first Wendel would have been twenty grand. It takes a lot of memory to have a higher sample rate, which gives you an 80kHz frequency response - today’s consumer units have only 20kHz. Just one snare beat takes 48k of memory. One crash cymbal takes $12,000 worth. We just used the brute force method so we could get it done. The new improved Wendel has a megabyte of memory, 32 megabyte hard disc, higher sample rates and it’s 16-bit.” Wendel II was used on much of Fagen’s 1982 solo album The Nightfly.

This parallel development of the sampling drum machine by the two Rogers almost parallels that of the earliest electro-mechanical rhythm machines. The drum machine was first mass-produced by Wurlitzer with their Sideman model in 1959, but that utter genius of early electronic music, Raymond Scott had also been working on his Rhythm Synthesizer, an electric percussionist which he finished in 1960. In naming his creations Scott showed all the humour and personality later displayed by Roger Nichols & Steely Dan, when he introduced the world to Bandito The Bongo Artist. But there had been other creations and private commissions prior to these mechanical marvels. Harry Chamberlin had finished his tape-loop-playing Rhythmate electronic drum machine and brought it to the marketplace in 1957. Chamberlin was already the inventor of the first sampler instrument in the tape-playing keyboard that bore his name — an instrument that was more famously copied in the UK as the Mellotron. But even before WWII we’d been given artificial, electrically generated beats when Léon Theremin built his complex and ground breaking device, the Rhythmicon in collaboration with Henry Cowell in about 1931 (just when the Ro-Pat-In Company brought out the first proper electric guitar, soon to be better known as the Rickenbacker Frying Pan). Of course Theremin would become more famous for another electronic instrument that you didn’t actually touch. Incredible isn’t it, that a mechanised drummer should have been made at so early a date? Of course long before we harnessed elastic-trickery people were generating complex movement with springs and gears - and the first programmable drum machine was described by Arab inventor Al Jazari in

The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices all the way back in 1206. We don’t know when the first drumming automaton was actually built, but it was certainly conceived by the beginning of the 13th century****.

Pearl Jam Not Squirrel Jam

Electronic sounds and big beats have always gone hand in hand. Back in 1981 when Pearl initially released the Sound Spice series there were five compact pedals: CO-04 Compressor, PH-03 Phaser, OC-07 Octave, CH-02 Chorus and OD-05 Overdrive; and three larger dual switch units: PH-44 Phaser, the AD-33 Analogue Delay and the the CE-22 Chorus Ensemble, which was an even more direct homage to the legendary Boss CE-1 than their old F-605. Pearl later added the DS-06 Distortion, AD-08 Analogue Delay, GE-09 Graphic EQ and then later still, the SU-19 Noise Suppressor, and also another rare-as-rocking-horse-shit drum pedal legend: the TH-20 Thriller. Yes indeed, the TH-20 Thriller “frequency exciter” was even rarer than it’s cousin the Boss SP-1 Spectrum, and equally beloved of keyboard players (crazy, I mean it’s so obviously a drum pedal). However the TH-20 had far greater user control than the SP-1. The Spectrum was a single, wide-band parametric EQ with two knobs. The Balance knob on the SP-1 set where you wanted the peak of your frequency curve to be boosted, within a range from 500Hz to 5kHz set by the Spectrum knob. The Balance knob on the Thriller meanwhile, was a wet/dry mix control - the other three knobs being marked as Frequency (from 600Hz to 7kHz), Colour and Multipeak. Rarity breeds myth and rumour has it at that the TH-20 was developed in consultation with the Porcaro brothers (two thirds of them anyway) while they were both sessioning on an album that went on to sell quite well by a former member of The Jackson 5. It’s further claimed that Pearl even stole the album’s name for the new pedal. And talking of intellectual theft, it may also have been another Pearl pedal with a feature stolen from the Moog designed Lab series amps. Because the TH-20’s Multipeak control is remarkably similar to the Gibson L-5 guitar amplifier’s Multifilter (patented by Bob Moog himself), a 6-way EQ filter boost for 1kHz, 1.37kHz, 1.9kHz, 2.63kHz, 3.63kHz & 5kHz, that was then mixed with the clean signal. I’ll say it again, “Uh, crank up the mids”. Whatever it’s plagiarisms might have been, Pearl’s 1984 Thriller was a very useful tone shaper that, as mentioned, was also taken up by keyboard players as well as drummers. A natural progression I guess if the story’s true that it was trialled by both Jeff and Steve P.

Technology moves apace and by the Nineties the use of drum effects pedals had been largely superseded by the digital sampler technology that Rogers Nichols & Linn had been experimenting with a decade earlier. But there were plenty of drummers still stomping on boxes. Of course for crunching up sampled drums you really had to use the Akai UniBass UB1 which added a harmoniser to it’s distortion circuit. If you were using an MPC60 from the off in 1988, it’s likely you would also have been crunching up it’s outputs with something or other in pedal form, so Akai decided to bring out a range of pedals they could package with their Music Production Centre. The UB1 was an octaver, adding one above, but you could also add a 5th above or a 4th below at the flick of a switch. Basically it was the old trick of chaining Pearl’s Over Drive with their Octaver. But of course the remarkable flexibility that was intrinsic to the runaway success of Roger Linn’s 16 pad baby (the MPC was the big brand reboot of his LinnDrum MidiStudio concept), meant that using proprietary effects pedals was not the way to get the most unique and individual sounds. Why process sounds after you sampled them when you could get the effected sound you wanted into the sampler and then always play it the same?

I mentioned a pedal by Slingerland earlier, with a certain Motorhead pedigree: but it was actually no more than a re-badged Ludwig unit. About the only effects pedal by Ludwig that anyone usually remembers was the Ringo-Lator, a very average sounding, though very early, ring modulator that might have passed entirely unnoticed had it not received an endorsement through the offices of Brian Epstein's NEMS Enterprises. The circuit in the aforementioned Rolling Thunder first appeared as the Ludwig Thunderbird in about 1970. It was an octave fuzz effect, nothing new there you might say, even for ’70. But what made it special of course, and the reason it is so beloved of Sludge and Doom guitarists these days (stick one through an old Laney AOR amp and you’re there), was Ludwig’s request to the circuit designer to make it shift an octave down, rather than the usual octave up. William F. Ludwig, like many early American instrument makers, and like many a son of Chicago, was also the son of German immigrants. The story goes that Ludwig played against a certain Thomas Mills in a competition of some sort and was deeply impressed by the volume and projection of Mill's novel, metal shell snare drum, bought from a company in Germany (that would soon take the now familiar name of Sonor). Apparently Ludwig pestered Mills to borrow the metal snare so he could copy it. William, along with his brother Theobald Ludwig, were sales agents for the Leedy Drum Co. through the shop they’d founded in Chicago in 1909. However William failed to persuade the otherwise innovative Ulysses G Leedy that metal was a suitable drum shell material. So Villi & Teo set up the Ludwig & Ludwig Drum Company to make them for themselves. Ludwig drums made significant advances (despite the First World War and Theobald unfortunately being claimed by the Great Flu Pandemic), and in 1920 the Ludwig Black Beauty was born.

The Tin Drum

By the end of the Roaring Twenties however, both the Leedy and Ludwig drum companies were bought up by C G Conn and moved to Elkhart, IN. Though initially kept as two separate product lines the Leedy & Ludwig Drum Co. would be amalgamated in 1951, and then bought back by William F. Ludwig four years later with the help of Bud Slingerland. Before buying back the name in 1955 Ludwig had been producing his drums under the name WFL since 1930. But Ludwig’s reputation as a percussion innovator actually began with the first decent drum pedal. We're talking a bass drum beater pedal here, rather than an effects pedal. You see it was only in the late Victorian era that musicians had begun to play a “set” made up of more than one drum, and to start using as many parts of their bodies as possible with which to hit them. Before the funky drummer came along you had to have a dozen guys (marching up and down in uniforms to make Sgt. Pepper jealous), with one piece of percussion apiece — like John Phillip Sousa did. So the development of a mechanical device that could transfer energy through a drummers feet, but still keep good time, was quite revolutionary. And indeed that 1909 design of Ludwig’s was their attempt to significantly improve on the functionality of an innovative prototype, probably the world’s first ever kick pedal, made in 1900 back in Germany by, yet again, Sonor.

Sonor’s heritage as a percussion manufacturer goes back to 1875, initially as Trommel-Fabrik of Weissenfels, until they trademarked the Sonor name in 1907. That history, as we’ve seen, includes the invention of the metal shell snare drum - one of which Sousa’s favourite drummer Tom Mills supposedly bought while on tour in Europe in 1900 and brought back to America. Made from a hammered brass shell with welded seam and also metal hoops, it was 6.5” deep and 13” in diameter. And thus the Heavy Metal genre was born. Sonor still make an aluminium shell Parade Snare named for company founder Johannes Link — a design that has been in continuous production since 1942, though perhaps we better gloss over just who was marching to those Parade Snares back in the 1940s. Go read Günter Grass instead. After WWII Sonor found themselves in the Russsian sector — Weissenfels, being just a few kilometres WSW of Leipzig. So they upped-sticks and in 1950 built a new facility in Westphalia.

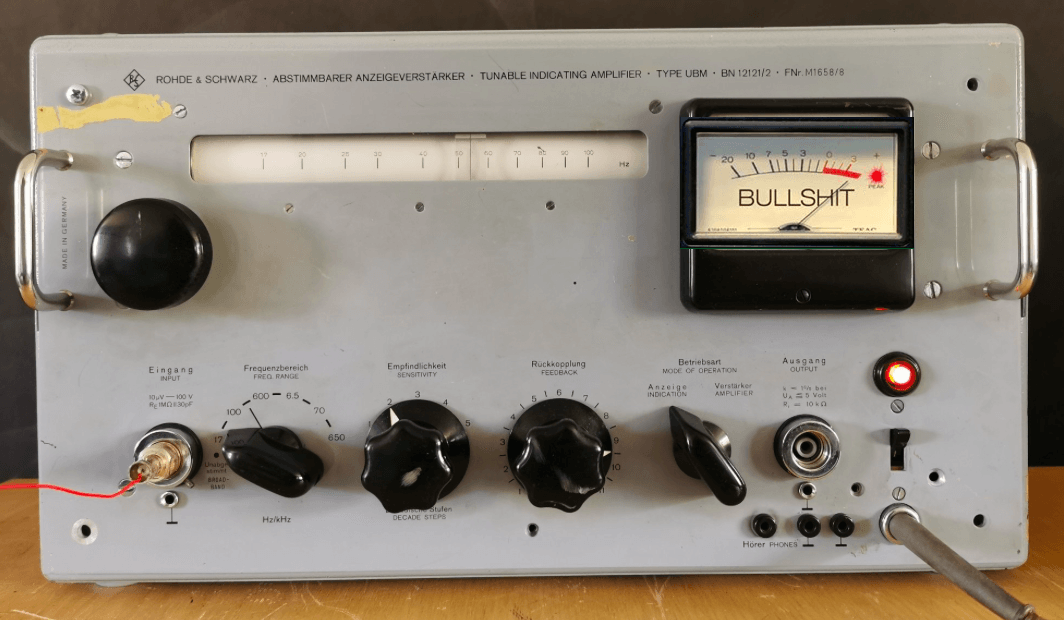

So where exactly did the Tonreich myth begin? Well in some ways it goes all the way back to the ‘50s with the experimental compositions of Karlheinz Stockhausen and in particular, his ground breaking opus Kontakte. The Sonor Tonreich was more than a mere micro amp (it was certainly in a much bigger housing that MXR’s M-133 unit), it was actually built around a series of 6 JFET pre-amps into Darlington pair transistors. In addition it had finely tunable low pass filters, dialed in with both rotary switch and potentiometer and it ran off a 24vDC supply. It was designed to emulate some of the sounds wrung out of a much more complex unit that Stockhausen had used and abused at the WDR Electronic Music Studio in Cologne as early as 1958. The Rohde & Schwarz UBM Tunable Indicating Amplifier was a valve amplifier with several bandpass filters, that was really a piece of test equipment used mainly in telecom and broadcast applications and which could handle signals as high as 650kHz, but more significantly, as low as 17Hz. The Tonreich generated great synthy sounds that could go exceptionally low, indeed into the subsonic range and it’s claimed that Kraftwerk’s Wolfgang Flür was a consultant during it’s development. Sonor set up a small workshop to hand-build the Tonreich but it was an expensive project and little thought went into marketing before it went into production. It was a diversification that Sonor were ill prepared for and production numbers were low - with a manufacturing run lasting less than 6 months. Had these pedals been farmed out to Schaller in the Japanese OEM model (Schaller's early ‘70s tremolo pedal is still a bench mark, we have one of those at New Cut too), the Tonreich might have had a longer life span and been better known to this day.

I think enough has been said to prove our point here. When you're looking for edgy urban grit and biting crispiness, those haunting mids and heavy low end whumps, you need to reach for the drum pedals. So remember — when your Krupaphonic-Starclassabian-Klone-JunkyThrummer profile won’t cut it, you need to get busy with the dirt box. If you’ve got this far without shouting at the screen well done! I must apologise for the tone of this blog, as well as the sense of humour and the various blind alleys and garden paths I’ve led you up. You see it’s the kind of joke roadies love - until they realise there’s a good idea spoken in jest.

“It’s such a fine line between stupid and…”

“And clever.”

“It’s just that little turn about.”

Indeed, that Spinal Tap subtle twist, the fine line between genius and cretin, that we in live music seem to walk with regularity. Those of you out there who know your stuff, or are old enough, will have cottoned on pretty quick to the jokes. I tried to slip in “embiggen” pretty early on to drop the hint and followed it up with a pretty bad joke at Carmine Appice’s expense — both of which I sincerely apologise for. And please note that any tub thumping has been for comic effect. There’s a huge amount of fiction in this piece of writing, but if it inspires you to do a little digging around you’ll find that most of the more surprising facts are, well, just that. Also I’m frequently shocked by the appalling amount of lazy journalism and wholesale text theft that goes on in online music related articles, so maybe someone will repeat some of this crap verbatim without further research — always entertaining.

When I started out in this business, if anyone had suggested putting distortion on drums it would have been met with the kind of ridicule reserved for doing Heavy Metal in Dobly. Back in the late Eighties we would joke that a poor guitar solo could be disguised with pedals, but that a poor drum solo had to do it with strobe lights. But as Hip Hop matured and its influence spread massively in studio production, fattening up drum loops from old vinyl or new drum machines became quite the art. By the nineties we were crunching up loops and beats before doing anything else with them. And if you want to see what can be done with a pedal these days check out the JHS Colour Box. In fact here’s a look at what can be done with the Version 2, which has nearly all the flexibility of the 500 Series rack version in a pedal chassis. So while this blog started out as a piss take — here’s a pedal being used on every instrument in the mix, and particularly on the drums.

I know, I’ve been ignoring drummers in my choices for blog subjects so far. Mainly because I’m not really an expert on things rhythm, I’m a guitar guy. Perhaps that’s why I took such a jokey approach with this one (though it also seemed to develop a comic mind of it’s own). I can set up a kit pretty fast and make it comfortable — and tuning it properly, changing heads, fixing hardware, all not a problem — but don’t ask me to play it. I set up a hire kit for drummer David Cola for some shows with Nicole Scherzinger at the end of last year. He flew into the UK, came to the studio, sat down at the kit… and then barely moved a thing. He was as surprised as I was about that — it became a talking point anyway. I think he changed the angle on the SPDS and raised it slightly. Check out David’s YouTube channel and his website to see what an incredibly versatile musician this young Berklee graduate is. I’ve looked after some pretty great drummers in my time as a roadie actually. Keith LeBlanc, Rich Thair, Tom Skinner, Paul Cook, Darrin Mooney, Frank Tontoh, Carlos Hercules, Cherisse Osei, Ged Lynch, Robin Goodridge, Pete Howard, Steve ‘Smiley’ Barnard, Sam ‘Blue’ Agard, and Eric ‘Boots’ Greene, to name but a few who were great as players, performers or just people.

* Lab Series amps were a solid state range designed for Gibson in 1977 by Moog — both Norlin companies at the time. The Gibson L5 has been favoured by BB King and Joe Bonamassa amongst others. Yes, you heard right, "solid state", "blues legends", same sentence. They had a warm creamy tone with loads of punch which like many of the early SS boxes comes from clever use of discrete components like Field Effect & Darlington transistors as well as Op-amps to mimic the architecture & time constants of their valve predecessors. Alan Holdsworth, Ty Tabor and Ronnie Montrose were also notable users of the L5. However the Moog Gibsons are not to be confused with the Lab Series 2 amps made by Garnet In Winnipeg, MB, which are very different beasts.

** In 1946, initially manufacturing music stands, before they started to make drums in 1950 as Pearl Industry Ltd.

*** I never worked with My Bloody Valentine but I looked after Kevin and Mani when I covered stage-left with Primal Scream on a couple of tours. Amongst the crew he was always known as Kevin-Bloody-Shields or sometimes Bagpuss. If I remember right, Kevin was using three amps and a pedal board the size of Berkshire. He had a Wah Wah that had more mini toggle switches on it than I have ever seen on any pedal ever. It looked like a robot hedgehog.

**** I know I’ve raised the bullshit bar pretty high in this parody of a blog, but truth is often stranger than fiction.

© Mark Vickers 22/08/2020.